On distance II: Literature and Catharsis

I quietly turned a page and paused to hear if anyone woke up. The dominant sounds were crickets’ chirps and the wind’s rattle through the leaves. I resumed reading, still alert to nimbly hide the crime object under the bed.

Mum had forbidden me to read Crime and Punishment and reasoned that I was too young; I could read it in a couple of years. I thought her concerns were just big words or abstruse sentences. I didn’t realize how deeply it could affect an eight-year-old mind. Besides, she’d borrowed it from a friend, and I didn’t want to miss that opportunity. Anyway, for two weeks, I’d wake up after midnight, grab Crime and Punishment from the stack of borrowed books, read, then put it back in the same place before anyone woke up.

This experience coincided with the TV showing a Crime and Punishment film — a Russian black-and-white movie that portrayed Raskolnikov, the protagonist, pale, melancholic, and scary, with prominent dark circles under his eyes. My punishment was having recurring nightmares for a while. Raskolnikov was chasing me with his ax hidden under his coat and I was running through my neighborhood as fast as possible to escape.

Thirteen years later, after unwrapping a birthday present, I faced Crime and Punishment for the second time. I thanked the friends who bought it together, but I wasn’t sure about giving it another shot. Recalling the first encounter, I’d feel uneasy to read it again; however, I wasn’t a child any longer, and I hadn’t understood the depth of the book. Moreover, I wanted to cherish my friends’ present. So, I went for it.

To explain what I mean, I need to touch on some parts of Crime and Punishment.

Reading it for the second time was an epiphanic experience. I felt catharsis throughout my mind as if I could sense all the electrochemical reactions in the brain. Using catharsis to describe the function of literature and art, Aristotle in Poetics says that tragedy should arouse pity and fear and thereby achieve catharsis of such emotions [Aristotle, Poetics, ch. 6]. But he doesn’t define exactly what catharsis is — is it purification, purgation, or clarification? The process remains mysterious and open to interpretation. Now I had a deeper understanding of how catharsis worked.

You are a young man with a promising future, but the door seems to be closing due to poverty. You have no money and are in debt to your landlady. She is an old pawnbroker woman, Alyona Ivanovna, who has no family except her half-sister Lizaveta. Cold-hearted and greedy, she is viewed by Raskolnikov and others as exploiting the poor through her pawnbroking. You’re in dire straits, watching your dreams disappear. You have no way to make money, your poor family can’t support your studies in Saint Petersburg any longer [he is a former law student], and there seems to be no way to stop the snowballing debt. What would you do?

At first, you might not consider killing the landlady, but desperation, coupled with the widespread contempt for her character, could nudge you to cut the Gordian Knot. As a reader, the catharsis happens when you put yourself in Raskolnikov’s shoes, grab the ax, and do the act of killing. You would feel your heart pounding, your mouth dry, thoughts and blood rushing to your brain. The lady is dead. You should feel that she’s not alive anymore. You should feel the pain of taking someone’s life, even the worst person on earth. This realization should shake you to the core. You should twist and twirl in agony, even avoid looking into your own eyes in a mirror. Then you’d go through the process of atonement. You wouldn’t be the same person, but you’d learn to live with it.

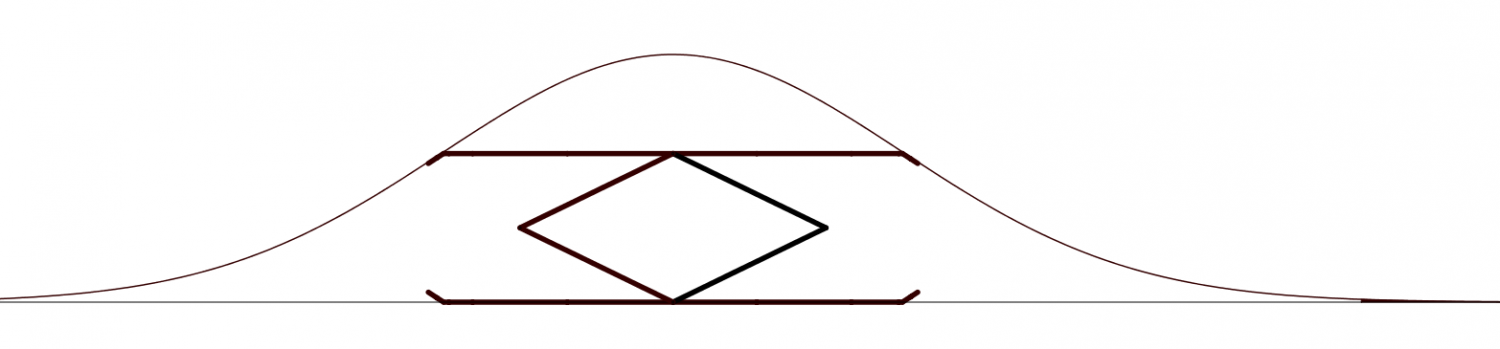

Don’t worry. It never really happened. You virtually experienced murdering a person. You lived a life in a book that could cost you many years in prison, or in some places, your life. You came out of this storm stronger, more mindful, and also more understanding. I’d see this process as vaccination: you get a small dose of weakened microbes to strengthen your immune system. That’s how I define catharsis.

The crucial point is while reading a book, you need to maintain a healthy distance, reminding yourself every once in a while that it’s a story. It’s like diving to experience life underwater. You need to come back to the surface every once in a while, or you might be consumed by the story itself. Apart from Don Quixote, the fictional epitome of those who couldn’t distinguish between stories and reality, Madame Bovary is based on a real case of a provincial woman whose life inspired Flaubert — she ruined her marriage and eventually took her life, chasing the passionate love she had read about in novels.

The first widely documented case of a novel’s dangerous impact was Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) (Goethe’s saga is worth an entire post). The story of Werther’s suicide sparked a wave of imitations — so many that the phenomenon is now called the “Werther Effect.” Young men dressed like Werther, and some even ended their lives in the same way. Napoleon himself admired the novel and reportedly carried a copy with him on campaign in Egypt.

That’s how I introduce literature or art to my students if the topic comes up. It can be cathartic as you get involved, but you need to be careful about maintaining that healthy distance, or it can have negative impacts, in some cases even irreversible ones.

I also warn that immersing yourself in the world of books might squeeze your social circle, because next to the planned and crafted sentences in books, most daily conversations have little chance to match the excitement and engagement. So, you should have a healthy dose.

If I could go back in time and talk to myself, the eight-year-old bookworm, I’d stop him from getting overdosed on Dostoevsky.

Categories: Journal